click/tap the image to view at full size

click/tap the image to view at full sizeWalter Lindrum – Fifty-seven world records, with some still standing today. Considered to be one of Australia’s all-time greatest sportsmen, Walter Lindrum was in a league of his own on the billiards table. His talent for the sport was a product of both genetics and environment, and his rise to the top is nothing short of fascinating.

Family Background

Success in the sport of billiards was in Walter’s blood. His paternal grandfather, Frederick William Lindrum I, was Australia’s first World Professional Billiards Champion, winning the title in 1869. Walter’s father, Frederick William Lindrum II, also showed great prowess in the sport, becoming the Australian Billiards Champion at the age of 20. He was also considered to be the greatest billiards player in the world by Walter and his older brother Frederick III, but chose to coach his two sons instead of touring professionally, an act that would change the course of sporting history. Walter’s mother, Harriett, was highly skilled at sewing and baking, winning numerous baking competitions in Kalgoorlie, his place of birth. He often credits his mother as his inspiration for the sport.

Early Life

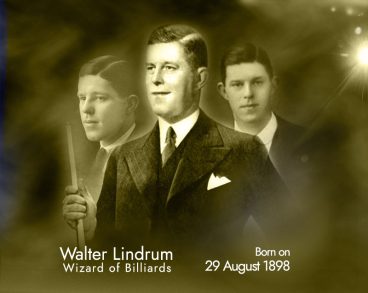

Walter Albert Lindrum was born on 29 August 1898 in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, with his initials being an ode to the state where he was born. His father taught him to play left-handed, due to Walter losing the tip of his right index finger in an accident when he was 3 years old. He spent most of his childhood practising the sport of billiards, up to 12 hours a day under his father’s coaching. This allowed him to play his first professional game at the age of 13. Within a few years, he was defeating his older brother Frederick III, who was a multiple-time national billiards champion. The two brothers refused to play each other for the national title.

Becoming the Greatest

During the 1920s, Walter’s standard of play was a level above all others domestically; he was already making breaks of over 1,000 on a regular basis by then. As a result, many players refused to compete against him, and so he turned to exhibition matches, mainly with his New Zealand counterpart, Clark McConachy. It wasn’t until 1929 and the early 1930s when Walter began to truly establish himself as the greatest billiards player of all time. Willie Smith, billiards world champion in 1920 and 1923, visited Australia and played three fairly competitive matches against Lindrum. At one match each, Walter was forced to forfeit the third match midway through it, due to the untimely death of his partner. However, Smith refused to accept the trophy, insisting it be awarded to Lindrum.

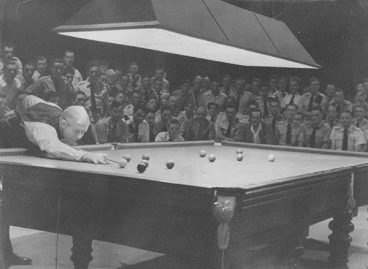

In September 1929, Smith, McConachy, and Lindrum departed Australia for a billiards tour in England, where Lindrum proceeded to dominate the sport. So much so that he often started matches by conceding as many as 7,000 points to his opponents, with games being played to 24,000 points. Word of Lindrum’s dominance spread quickly to the Australian cricket team – which Donald Bradman was a part of – who were touring England at the time, and they would attend some of Lindrum’s matches. Many comparisons were made between Lindrum and Bradman over their illustrious sporting careers, with the former being referred to as the “Bradman of billiards”, and the latter referred to as the “Lindrum of cricket”. Bradman even considered Lindrum to be more dominant in billiards than he himself was in cricket, such was the esteem in which Lindrum was held.

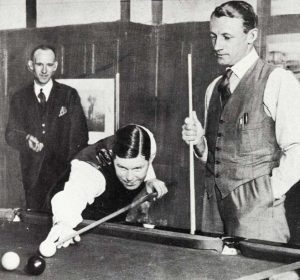

In February 1931, during the peak of his powers, Lindrum was invited to Buckingham Palace to give a billiards exhibition for King George V and other members of the Royal Family. King George V presented Lindrum with a pair of gold and enamel cufflinks decorated with the royal monogram. These formed part of Lindrum’s essential attire for the rest of his billiards career and daily life.

With a royal touch to his attire, Lindrum reached new heights in billiards, with himself describing the experience as being “a lone cueman on a mountain peak so solitary”. In 1932, Lindrum achieved a record break of 4,137 in a match against Joe Davis, the four-time world billiards champion. The billiards governing body had to change the rules of the game in response to the level of play Lindrum operated at. Not that it mattered at all to him – he proceeded to win the World Professional Billiards Championship the next year, in 1933.

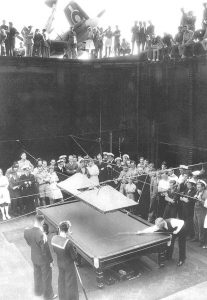

Lindrum successfully appealed to defend the championship in Australia the next year, due to his skill and success, with the match held in Melbourne. It was organised to coincide with centenary celebrations for the city of Melbourne, which garnered plenty of interest in the championship match. The challengers for the 1934 World Professional Billiards Championship were Clark McConachy and Joe Davis, and Lindrum successfully defended his title, with Davis finishing runner-up. Lindrum held the title until his retirement in 1950, due to a lack of challengers, which coincided with snooker overtaking billiards in popularity.

Lindrum’s Legacy and Later Years

In later life, Lindrum moved away from competitive play and focused his efforts on charitable endeavours. He performed around 4,000 exhibition matches during the Second World War, raising money for the war effort through such means, in addition to the revenue from his book Billiards. Lindrum raised an estimated £2 million over his lifetime for charity. For his efforts, he was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 1951, and an Officer of the Order (OBE) in 1958.

Some of Lindrum’s records include the record break for each country he has played in, the fastest century break (46 seconds), and 1,000 points in 28 minutes. There was some criticism about his style of play, being somewhat mechanical and lacking in style, but one of his greatest rivals thinks otherwise. Tom Newman, six-time world champion, wrote: “it is the greatest injustice you can do to Walter to call him a scoring machine. Nothing could be more unlike him. He is showing you everything the beautiful game can show.”

Lindrum passed away at the age of 61. Following his death, Sir Donald Bradman wrote to Lindrum’s niece Dolly: “in my opinion, he was not only the greatest billiards player who ever lived, but he was also the most modest of great champions.” Walter Lindrum received a state funeral in Melbourne, attended by 1,500 people, with his resting place in Melbourne General Cemetery being a monument of a billiards table complete with balls and cue. Over 50 years later, Lindrum’s grave is reportedly the most visited grave in the cemetery.

Please read Walter Lindrum’s “Timeline“, which unveils his unique upbringing, illustrious career, and philanthropic endeavours in his retirement.